|

The Wanderers

(Enjoy the Silence #2) by F.J. Campbell PART ONE November 1990 Danny As I drove back into Middon-upon-Frome, I wound down my window, partly to rid my VW camper van of the smell of stale alcohol, and partly so that I could breath in the air of my home town. I felt like I’d been away for so long, when in reality it’d only been a couple of months. I slowed down and scanned the familiar streets in the near darkness. I loved this place, even though I knew it was a dump; even though I left voluntarily for months at a time. Returning to Middon, I always felt like the town had been waiting for me. Usually, I stopped in at home to see my mum, Julie. Then, after a quick hello, I would knock next door to see Heather, Alistair and Mrs Sullivan. After that, we’d walk to the pub, to see Matt Lorenzi. This time, it was different. This time, I had to get my passenger home before they noticed anything was amiss. I was hoping that Mrs Sullivan wouldn’t be at home tonight. Ali was at Uni. And Lorenzi could go to hell. I listened to the steady hum of her breathing. The traffic lights at the southern end of the High Street turned red and I slammed my foot on the brake. I glanced over my shoulder. Still asleep. ‘Good evening Daniel,’ barked a voice at my elbow. ‘How are you, young man?’ Shit. I hadn’t noticed Mr De Vere, who was now peering in through the open window. Gulp. This was bad news. ‘Um. Hello Mr De Vere. How are you?’ ‘Fair to middling, m’boy, fair to middling. Bit of back trouble, swing’s off I’m afraid. Home for half term, are you, eh?’ ‘Er. Yes, that’s right, half term.’ I was sweating. I had to get rid of De Vere, before she woke up and gave herself away. ‘Anything wrong, Daniel? Have you got someone back there?’ He tried to bend his head past me, so I shifted in my seat to block his view. He peered at me. His face was so close, I could smell whisky on his breath. At least he wouldn’t catch a whiff of the vapours in my van. ‘Got a gal in there, have you, young lad? That’s it, isn’t it?’ He slapped the side of the camper with a gruesome wink. I blushed. ‘Righto, I’ll let you get off then. Wouldn’t want to delay you, what ho.’ With one last attempt to see around me, he shuffled off down the High Street, in the direction of the river. I breathed out. Fuck, that was close. When the lights turned green, I put my foot down and drove past the Rainbow Café, noticing a girl I didn’t know sitting alone at a table by the window. I caught a glimpse of her profile, dark hair and a long, straight nose, but nothing more. I passed Ladbrokes and a boarded-up estate agents next to the SPAR. After that was the library, its shuttered doors closed and covered with graffiti. At the top end of the High Street, I turned left at the derelict hotel, along the river, and then at the bridge, left again, into Bridge Lane. I drove straight past my front door, checking that there were lights on, and parked instead at the gate to the Sullivans’ house. Every window was dark. There was a good chance I could manage to get her in before her mum came back. I cut the engine and climbed out, walking around the side of the camper furthest away from our house and quietly slid open the side door. I stepped up inside and put my hand on her shoulder, shaking her gently. She stirred, blinked her eyes open and groaned, groping her hand and grabbing mine. She hauled herself up just in time to reach the bucket that I held and was silently sick into it. Again. I watched the familiar sight, trying not to laugh, which she hated, then looked out of the window to check the two houses and so she would know I wasn’t watching her, which she also hated. ‘Danny?’ Her voice was husky and hurt. I turned my face back to her. ‘We’re home.’ ‘Is she there?’ ‘Don’t think so. It’s dark, and at mine the kitchen light’s on. Could be they’re getting sloshed.’ I pulled her up with our joined hands and slung her arm around my shoulders. She was warm and soft and smelled really, really bad. She pulled away from me and scowled. I chuckled. She stepped towards the gate and lifted it slightly as she swung it open, to make sure it didn’t squeak. At the front door, she lifted a plant pot and swept her hand under it. The key bounced down the steps and clinked twice, sounding louder than it really was in the quiet of the street. She snapped it up in her hand and froze. After a moment, she turned the key in the lock and passed through the door tentatively. She turned to me, made the sign with her hands on her cheek that she needed to sleep, mouthed ‘Thanks,’ and disappeared inside. I sighed, left the step, grabbed my bag from the camper, closed the door with a bang and turned the key in the lock. I hadn’t even reached my front door when Julie opened it and flung her arms around me. Definitely sloshed. I kissed her flushed cheek and ushered her back inside. Mrs Sullivan was there, two wine glasses on the kitchen table. She stood up and hugged me too. ‘We thought you’d have been back yesterday; you said the third, didn’t you? Why didn’t you call?’ asked Julie, beaming at me. ‘Are you hungry? Would you like some wine?’ ‘Is there any left?’ I asked with a grin. ‘Cheeky.’ ‘Wine would be great. I’m not hungry yet, thanks.’ I fetched a glass from the side of the sink and pressed the nozzle on the wine box. I sat down next to Julie and opposite Mrs Sullivan and smiled at them both. Julie stroked my hair out of my face. ‘Your hair grew.’ ‘That can happen.’ Mrs Sullivan said, ‘Are you coming tomorrow night, to the bonfire?’ I nodded. ‘That’s the plan.’ ‘Do you think Heather will be all right by then too?’ Mrs Sullivan gave me a meaningful look over the top of her glasses. Oh. I slumped back in my chair and looked up at the ceiling. ‘We weren’t born yesterday, you know.’ Julie frowned at me. Mrs Sullivan pushed herself up from her chair and sighed. ‘You don’t have to go, she’s fine. She just needs to sleep. Honestly.’ ‘Daniel. I’m Heather’s mother. You two, you can’t fool me.’ I shrugged. ‘I’m not trying to fool you. Any more. But she called me from a friend’s house and I picked her up.’ The lie slipped out smoothly. ‘No big deal. She’s not going anywhere until the morning.’ I raised my eyebrows hopefully at Mrs Sullivan, who sighed and sat down again. ‘What was it this time?’ ‘Argument with Matt.’ Mrs Sullivan exchanged a look with Julie. ‘What about?’ ‘Maybe you should ask her. In the morning.’ I sipped my wine, which I didn’t really want, and listened to the two women talk. Mrs Sullivan was complaining about the graffiti on the Welcome to Middon town sign. ‘Who would do such a thing? It’s atrocious. The youths in this town need to start taking responsibility for their actions. They spray this graffiti and then wonder why no one will employ them.’ Julie nodded. ‘It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.’ ‘They’re just bored,’ I protested. ‘It’s soul-destroying, living in a place like Middon, with no reason to get out of bed every day. They feel like their lives are meaningless. We’re talking about teenagers – don’t you find that shocking, that someone my age should feel like that? The graffiti is their way of expressing themselves.’ ‘If they’re so bored, then they should get a job.’ ‘What job? Where? You want a job, you have to leave Middon. Everyone here is just waiting around, waiting to leave, waiting for something to happen to them, waiting to get arrested, waiting to die. It grinds them down.’ Mrs Sullivan shook her head. ‘That’s no excuse. The things that happen here, right here in Middon-upon-Frome, are staggering. An elderly lady was mugged, in broad daylight, last week. And every year for the last decade there’s been an increase in crimes like assault and grievous bodily harm. Are you saying that it’s acceptable? Just because they’re bored?’ ‘No, I’m just-’ ‘Daniel, you manage to go to school and earn money. You’re not out committing crimes and taking drugs on the streets every night.’ ‘Yeah well I’m lucky. I’ve got you two breathing down my neck.’ I finished my glass and listened to them trying to set the world – or at least Middon – to rights. Despite the defence of my fellow youths, I detested this about my town. The violence – especially against women - was a permanent fixture of our lives and we’d all been taught from an early age to not venture into town alone at night. The irony that I’d just picked up Heather from a potentially dangerous situation and then lied about it to her mother was not lost on me. I yawned. ‘I’m exhausted, I think I’ll turn in.’ I kissed Julie and trudged to the door with my bag over my shoulder. ‘Have you got any washing?’ ‘In the morning,’ I repeated, laughing kindly at her. My room was just as I’d left it. I drew the curtains back, glancing over and up to Heather’s attic window, which was dark. For a while, I lay fully clothed on my bed and let my thoughts drift back to last night. * I’d been driving along the A354 and had seen her on the side of the road, walking unsteadily, wearing an unfamiliar dress and a feather boa wrapped around her shoulders. I didn’t have to look twice, I’d recognise her anywhere. I pulled over and shouted at her over the roar of the traffic. ‘Heather. What the fuck are you doing here?’ She jerked her head towards me, startled, tore open the passenger door and clambered in, grinning dozily at me, her eyes wild and glittering, her hair plastered to her head. She had no shoes on. Unbelievable. I pulled back onto the road. ‘Dannyboy, it is quite simply grand to see you,’ she burbled. ‘I was just trying to hi… hi… have you?’ I reached behind my seat and retrieved a bucket, handing it to her. She was sick into it. ‘Sorry,’ she mumbled, smoothing her hair off her face as best she could. She was quiet for a moment. ‘Grand. To see you.’ I was speechless. I turned off the road, pulled over in a side street and killed the engine, staring straight ahead until she managed to explain herself. ‘Can I sleep, please?’ she asked in a small voice. ‘Not before you tell me what the fuck you are doing at two o’clock in the morning, partially clothed, off your head, in the middle of nowhere.’ ‘It’s a long story. Sleep? Please?’ ‘Where’s Lorenzi?’ She slammed her head back against the headrest and groaned. ‘You are so stubborn. He’s at a party. I left him there. We broke up.’ How many times had I heard her say that? ‘He let you leave, on your own, in the middle of the night? I’m going to slaughter him.’ ‘It’s very chilval… chirelv… kind of you. But there’s no need. I took care of the slaughtering myself, before I left.’ I stared at her. ‘What? What did you do?’ ‘Not entirely sure. But I think he might have a black eye later on today.’ Silence. She shrugged. ‘He deserved it.’ ‘No doubt. What was it this time?’ ‘Just the usual. I’m done, Danny, that’s it. Time to say goodbye to Matteo Lorenzi. Time to…’ she waved her hand slowly away from her… ‘move on.’ ‘Right.’ I took a deep breath, a thought forming in my head, then quickly thought about something else. I pushed my hair out of my face. ‘OK. Sleep, then.’ She climbed into the back. ‘Here, take this, just in case.’ I handed her the bucket. ‘Lie on your side.’ ‘Will do.’ She flopped down onto the bed and covered herself with the blanket. A sigh, a rustle and then her breathing slowed. She must have been exhausted. I turned on the ignition again and pulled back out onto the road towards Middon. My anger towards Heather faded and my breathing returned to normal. I had her now, she was safe, no one could hurt her. At the heath, I parked the van and slept myself for a couple of hours in my seat, my jacket pulled up over my shoulders. Late morning, I woke and made coffee on the portable stove. I toasted some bread and sipped at my coffee, watching her sleep. She’d be out for a few hours yet and anyway, I wanted to wait until later in the day to get her back home. I looked at her, peaceful in her sleep, and a lump came to my throat. If what she said was true, if she and Lorenzi were no longer together, well thank Christ for that. There had been an inevitability about Heather and him, and at the time it had started, the summer before last, I’d eventually resigned myself to it, told myself that the sooner it started, the sooner it would be over. Lorenzi was irresistible to girls. Heather was a girl. It had taken him a while to get to her, but get to her he had. She’d told me then that they were just fooling around, that it meant nothing. She’d said they were only kissing and that she didn’t plan on sleeping with him. Maybe that was true at the time, but I was sure that wasn’t the case any more, because I knew Matt Lorenzi and it wasn’t possible that he could go out with a girl for that long without having sex with her. Three and half minutes was about the usual time before girls had sex with him. But I couldn’t ask Heather because we’d argued about it then, and we’d said some terrible things to each other. Now we skirted round the subject. I dreaded Heather getting hurt by that dickhead. Nothing I’d said had made any difference to her. Once, when I had told her that Ali thought Lorenzi was “something she needed to get out of her system”, she’d agreed. She’d even said that he was out of her system. But since then, they’d got back together. I shivered at the thought of what Heather’s system had in it now. The longer it went on, the more I worried about how much he was going to break her heart. Lorenzi was good at breaking girls’ hearts - there were hundreds, maybe thousands of them, lying around Dorset, gasping their lasts. And now, apparently, it was over. Again. I wasn’t buying it, though. This wasn’t the first time Lorenzi had flirted with other girls, even been caught red-handed by Heather, but he’d always talked his way out of trouble and she’d always forgiven him. True, she’d never hit him before. But she was hammered this time, and I knew that anything could happen when she’d been drinking. She didn’t drink very often and she didn’t drink very much, but every now and again, Heather forgot that she was a lightweight and she always ended up doing something stupid, then emptying the contents of her stomach. Every time. I finished my coffee and then opened a drawer quietly, moving aside an old but treasured photo of a sleeping Heather and took out my camera. I dropped down onto the heath from the camper and spent a few hours in the weak sunshine, never straying far from her in case she woke up. When I returned to the camper, I made more coffee and settled into my seat again with a battered old copy of Schindler’s Ark and a cassette recorder, pressed the red ‘record’ button and read quietly but clearly into the machine until late in the afternoon, stopping to make myself some more toast and scrambled eggs for lunch. She slept on. I’d seen her asleep before, of course I had, we’d been friends and next-door-neighbours since we were babies. I loved to watch her face when she was asleep. She was so pretty, but she wasn’t one of those girls who was aware of their beauty. If she saw you looking at her, really paying her attention, she’d make a face or turn away. The best time to look at and to photograph Heather was when she didn’t know you were looking. I drank in my fill now - her sweet face, her soft skin, the freckles on her nose we’d once tried to rub off with sandpaper, her hair all messed up (when was it not?), her mouth, her lips I’d once kissed, in an inexplicable, never-to-be-repeated moment of lust mixed with sorrow, that had thankfully not ruined our friendship but rather strengthened it, allowed us to let go of each other and spend some much-needed time apart. That Kiss had been two summers ago. No harm done. Just friends, trying out stuff. All in the past. When the light began to fade again, I drove slowly into town, past the sign that read ‘Welcome to Hell’. * The Wanderers will be available soon.

2 Comments

Which books can I use to lure my unwilling teen back to loving reading?

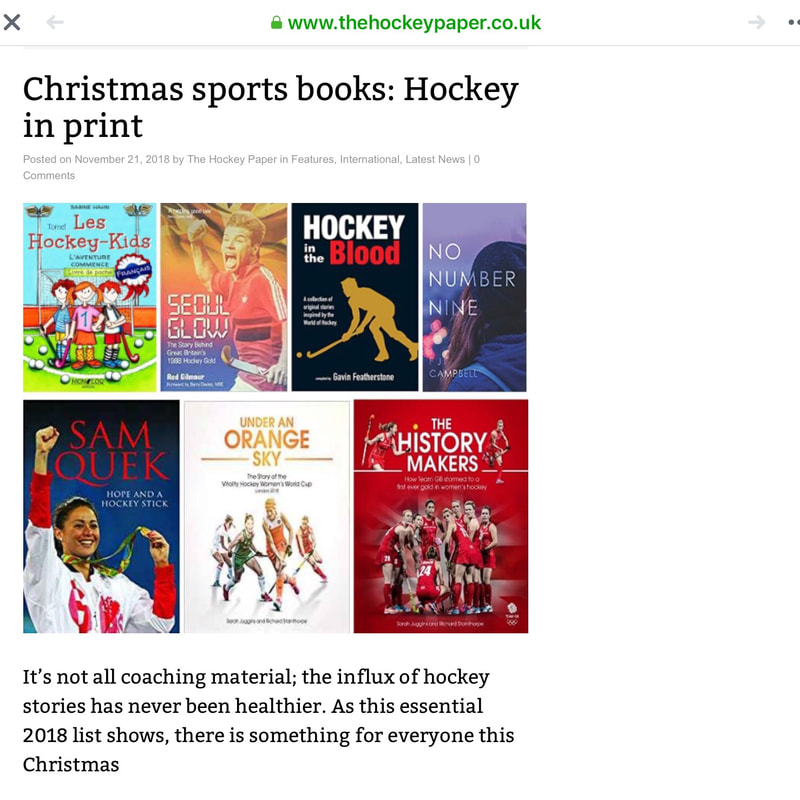

We all know the benefits of reading, and primary schools do a great job of encouraging our children to love books. But often when they make the switch to secondary school, pre-teens and teens lose that love and parents start to despair. When I tell friends and acquaintances that I’m an author and two of my novels are for ‘young adults’ (YA), they prick up their ears and ask me all about the books. That’s wonderful and many people I’ve met have bought a copy of The Islanders and Enjoy the Silence for their teens, who’ve loved them. But what I also tell them is this: that good writers must also be avid readers, and what we read informs our writing, and that I spent two years of my adult life reading only YA books. What those two years taught me is that YA books these days are so different from the books that were available when I was a teenager (in the 80s and and 90s) and that the choice nowadays is enormous and excellent. Back then, I can truly only remember one series designed for young adults, Sweet Valley High, and I raced through a few of those books before abandoning them for the much more satisfying classics. My teens were spent reading Pride and Prejudice, Vanity Fair and Wuthering Heights (as well as Tintin, anything by Jilly Cooper and The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole). Nowadays there are YA books that are brilliantly written and cover a range of themes that are perfect for challenging the minds and catching the imaginations of today’s teenagers. Children might start off with Harry Potter and then graduate to The Hunger Games, and they’re great for a bit of escapism, but after that you can find a whole host of books that will blow their teenage minds. Notable successes in my house have been Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, which is set in a depressing and dangerous world where everyone prefers to live in a virtual reality; and Noughts & Crosses by Malorie Blackman, where the world is run by the Crosses, who are black, and white people are referred to as Noughts and are discriminated against. The world in Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker is rotating more slowly every day than the last one, with devastating effects on wildlife, crops, and a teenager called Julia living in a Californian suburb. All of these books have science fiction settings; but they nevertheless deal with normal, personal stuff like friendships, first loves, grief, vulnerability and courage. Real-world problems like racism and sexual abuse are covered in books like Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give and Jenny Downham’s You Against Me, in which the main characters are the sister of a rapist and the brother of the girl he raped. Sexual abuse is also a theme in Fredrik Backman’s excellent Beartown, and transsexuality is sensitively and beautifully addressed in Lisa Williamson’s The Art of Being Normal. If any parents shy away from giving these sorts of books to their children, then perhaps they might consider whether it is better to learn about these tricky topics in real life or in the safety of the pages of a book. Fiction can transport children and young adults across worlds where they haven’t (yet) travelled and help them experience times that they will never see. Historical fiction and stories set in third world countries will carry teenagers beyond their own comfortable, safe lives and expand their horizons, without them even knowing. The Taliban Cricket Club by Timeri N. Murari’s heroine is a young woman living in Afghanistan; Trash by Andy Mulligan is a story set in an unnamed third world country about a gang of boys who pick through giant rubbish sites to make a meagre living; and Things a Bright Girl Can Do by Sally Nicholls is about three teenage girls who fight for the female vote in pre-first world war London. They are all astounding and are the sorts of stories that will remain with your teenagers for a long, long time. The list is endless but what I love about YA fiction is that nothing is taboo, which certainly never used to be the case. There’s more swearing, more sex, more brutality, more bullying, more crime and more death in modern YA books than ever before. Editors and publishers have let their authors have free rein and the results are fabulous (literally). Some of this will have your teenagers nodding sagely and saying, Yep, I’ve seen that happen, and some of it will make them flinch, or cry; but either way, what happens in these books will make them think about the complex rights and wrongs involved, and help them decide what kind of people they want to grow up to be. So it’s a win-win, right? All of these YA books could be read and enjoyed by both girls and boys. I don’t believe in targeting a book at one gender only; I think boys can benefit enormously from reading a book written from a female perspective, and vice versa. Imagine having a best friend of the opposite sex, who tells you exactly and in minute detail how it feels to be him: to speak to the girl he fancies, to have his first magical kiss or first embarrassing sex, to be confused about his sexuality, to live in constant fear of not being cool enough. All the good, bad and ugly things about being a teenager - a handy self-help manual wrapped up in a story. On those days when parents struggle to connect with their teens, and when they mock you and you can’t get them to open up, it’s always worth trying to talk to them about the book they’re reading. If you’ve read it too, either just before or just after them (or borrow two copies from the library and read it simultaneously), you can ask them which bit they’re at, and if they like this character, and did they see that twist coming because you certainly didn’t. And when you’ve both finished the book, you can download the film of it and tut together at all the unnecessary changes to the plot and character names. Fun for all the family! Here's the first chapter of Enjoy the Silence for you to read and see if you like it.

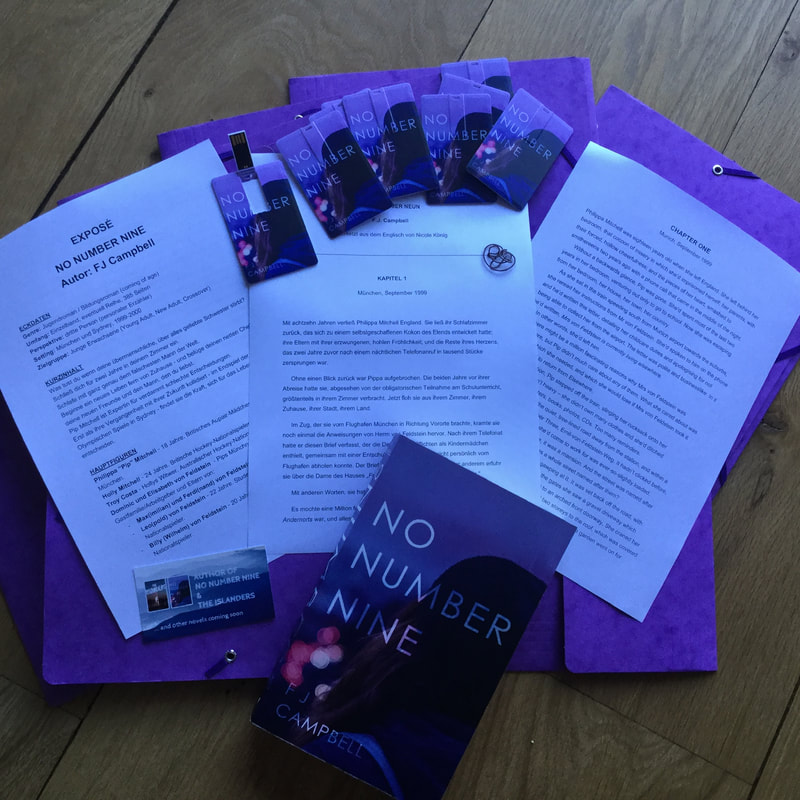

* Part One Summer 1987 Heather First day of the summer holidays. That feeling: eight weeks of freedom, everything waiting for you so that it could begin properly. These holidays were going to be the best ever. Danny, Ali and I, we had plans: camping, hiking, all the usual. Learning to surf. Practising new swear words. Talking till our heads dropped off. Lying in the dark together, listening to each other’s smiles. I broke up first, so Mum drove us to London to collect Alistair from his boarding school. The next afternoon, when Middon Comprehensive kicked out, Ali and I walked along the High Street, past the town hall, up the hill towards the southern end of town, through the dodgy part of Middon-upon-Frome until we got to the Comp. I had butterflies in my stomach, in my fingers, my feet, everywhere. We got there just in time to hear the bell ring inside the building and then there was a roar, the doors crashing open and, like a river breaking its banks, out flooded hundreds of kids. The first ones out were Ali’s age - the fifth formers, no more school for most of them. They were throwing their books in the air, leaving it all behind forever. One of them set fire to his books - a teacher scurried over with a fire extinguisher and put it out before escorting the boy to the front gates by his collar. It was like something out of Grange Hill. A few of the kids Ali and I knew from primary school shouted hellos. Jez and Sean Willemsen ran past us, stark naked. Most people tend to ignore Jez and Sean; they’re always doing wacko stunts like that. They say it’s because they grew up on a farm, so they’re as close to animals as humans can be. I didn’t know where to look. There were bits and pieces swinging all over the place, pale backsides, hairy front bits, I couldn’t look up or down and they seemed to be everywhere, so I looked at Ali. He was laughing at them, also maybe a bit at my embarrassment. His head was tipped back, his hands on his stomach, his mouth wide open. When Ali laughs, you can’t help joining in. Another teacher ran out into the car park, shouting and shaking his fist and the Willemsens scarpered. Nessa Chapple and Debbie Cowley waved and came over, nudging each other and giggling. They had colossal crushes on Ali, who smiled at them in his friendly-but-not-too-friendly way. ‘Vanessa, Deborah. How’re you?’ ‘Fine thanks, Alistair.’ ‘Your hair looks nice,’ he said to Debbie. She blushed and they both collapsed into giggles again. I rolled my eyes at them and they hooked arms and wandered off. No one ever fancies me, not like all the girls in Middon fancy my brother, but in case anyone ever decides to, I’ve been practising my friendly-but-not-too friendly smile. You never know. ‘Danny’s taking his time,’ said Ali, squinting, his eyes searching the faces in the crowd. ‘Is that Petey? Petey! Hey, man. How’s it hanging?’ ‘Ali Sullivan, as I live and breathe. Long time, no see. Hi, umm, hi… Heather.’ Petey Howard is Danny’s mate from school, tall and gangly with pale skin and transparent sticky-out ears. He’s one of the soundest boys I’ve ever met, but excruciatingly shy with girls, even me, whom he’s known his whole life. Nessa likes to tease him, she’s always pretend-flirting with him, and although I feel sorry for him, it is quite funny to watch him sweat and stutter. Poor Petey. Ali said, ‘Seen Danny?’ ‘Yeah, he’s just coming, he knows you’re here, he’s just talking to Patch.’ Patch is the Headmaster at Middon Comp, real name Mr Robertson or Richardson or Robinson, I can never remember. He has weird skin - hence Patch - blotchy and flaky, all over his face and neck, even on his scalp. It’s something to behold. ‘Have you heard the news - about the Lorenzis?’ Ali said, ‘What about them?’ at the same time as I said, ‘Who are the Lorenzis?’ Ali turned to me. ‘You remember Matteo? He and I used to hang around together at primary school. They moved away… what, maybe about five years ago. To Weymouth. Mr Lorenzi had a bunch of nightclubs there and along the coast.’ ‘Oh, them.’ I did remember Matteo Lorenzi - small, dark hair, smiley, good at football; his dad - fat, beardy; his mum - big hair, very glam. Everything else was a bit vague though. Maybe Danny would remember him better. Petey said, ‘They’re back. Arrived last week. Someone said they’re going to run The Wanderers pub again.’ ‘Cool. I’ll swing by tomorrow.’ While Petey and Ali talked - something about Petey’s dad who’d lost his job and Ali knew someone who knew someone who might be able to give him work - I kept glancing at the school doors, where the torrent of kids had turned into a trickle. I scanned the outside of the building - a flat roof, five storeys with rows of identical classroom windows, separated by three vertical faded beige panels, the lower levels of which were covered in graffiti. It looked grim, even in the July sunshine, like an East German prison. I’d never actually been inside the building. It squatted in a concrete car park and playgrounds, now covered in litter and paper and the Willemsens’ abandoned clothes. ‘There he is! Hey, Danny. Take your time, why don’t you?’ Danny walked up to us, the smile splitting his face. The top button on his school shirt was undone, his tie loose, shirt untucked on one side, sleeves rolled up. ‘Sullivan. Good to see you.’ He slapped Ali on the back. ‘Hi, Heather.’ He put his arms around me and squeezed really hard. ‘Ow. We’ve been waiting for ages, slowcoach. Come on come on come on. I want to go to the river.’ He smiled again at me. ‘Sounds like a plan.’ He took my hand and we started walking out of the gates. Most of the kids had dispersed now, Petey said bye and the three of us carried on towards the High Street. Down the hill at the river, we turned left by the derelict hotel and a minute later we were at the turning for Bridge Lane. I tried to turn left into it, but Danny pulled my arm. Don’t you need your swimming stuff? Already in my bag. You? I twanged my bikini out from under my T-shirt. Ali said, ‘Hey. You two. Where are you going? Don’t you need… oh. You did that thing, didn’t you?’ He tapped his head. ‘What? How? Oh nevermind. I need to get my stuff.’ He looked at me, straining to get on to the river. I’ll see you there, OK?’ Ali broke into a jog, towards our house, which was at the end of the cul-de-sac; a converted farmhouse with a huge garden that was Mum’s pride and joy. Next door, in one of the smaller farmworkers’ cottages, lived the Greens - Danny and his mum Julie. Ali swung open the gate and disappeared from view. Before we walked on, I glanced to the right, towards my school: Fromedale Ladies’ College. Across the bridge were high stone walls and an ornate gate, and through the fancy bits, you could see all the way up a tree-lined driveway to the main school, an eighteenth-century Queen Anne mansion surrounded by two hundred acres of school grounds, woods and formal gardens. It looked like something out of a Merchant Ivory film. It was beautiful and elegant and I absolutely hated it. I looked away. Wouldn’t need to walk that way for another eight weeks. Danny and I followed the river to the west, away from town, talking and not talking, it didn’t matter. All that mattered were the weeks and weeks stretching ahead of us, every day free, every day together. Heaven. We found our usual spot by the three weeping willows and I stripped down to my bikini, sat with my feet dangling into the cool water and sighed with happiness. Danny crashed down beside me. I searched his face as he tilted it up towards the sun. I hadn’t seen him since half term, so I wanted to get the new picture of him straight in my head. His hair was a bit longer than usual, it was a sort of muddy brown, not quite blond, and it fell over his ears. He had a few big red spots on his forehead and a painful-looking one on his chin. There were some whoppers on his neck too, at the back. I wondered if that was why he hadn’t taken off his shirt. We were the same age, Danny and I - our fourteenth birthdays were at the end of June, his the twentieth, mine the twenty-first - so if he was starting to get zits I thought I’d probably get them soon too. It doesn’t necessarily work like that. You might not get them at all. How d’you know? Danny shrugged and said out loud, ‘Helps to have a nurse as a mum. Julie told me that it runs in families.’ Danny called his mum Julie. Imagine the nerve - my mum would never have allowed it. ‘So did she have bad acne? When she was your age?’ ‘Nope. Maybe my dad did, though.’ ‘Ah. Great. Your non-existent dad. We’ll ask him, next time we don’t see him: “Were you a spotty youth?”’ Danny laughed. ‘I’ve got a bunch of other questions I’d prefer to ask him when I next don’t see him.’ ‘Like “What’s your name?”?’ ‘For example.’ ‘Do you ever ask your mum about him? I mean, she does know his name. Doesn’t she?’ He shrugged. ‘It’s never bothered me that much. It doesn’t matter anyway, what his name is. What difference does it make? I’m fine with everything how it is now - just me and Julie. Same with you and Ali and your mum, yeah?’ Ah. Yes. My non-existent dad. ‘Mmm. Except we do at least know our dad’s name and he managed to stick around for a couple of years after I was born. But you’re right, it doesn’t matter at all. Hey - maybe you were an immaculate conception. You’re the spitting image of your mum.’ There was a whistle behind us and we saw Ali waving from the bend in the river. But he wasn’t alone. With him was another guy, about the same age, not as tall as Ali but with athletic, deeply tanned legs and muscley arms. He had short dark hair and as they got closer I saw that he was spectacularly good-looking. I don’t think I’d ever seen anyone who looked like him before. He was sort of perfect. Like a film star. Danny, who’s that? Duh. It’s your brother. Ha ha. Who’s the other one? You really don’t recognise him? I glared at Danny. He ignored me. He was looking at Ali and the other guy, who was so close now you could see his square jawline and dark brown eyes. I was in a bit of a tizzy by then, I didn’t know where to look, not at the film star, not at Danny, who was for some reason being a prat, and so I summoned up my most normal smile for Ali. That was about all I could manage though. I couldn’t seem to get any words out. There was a tiny moment of awkwardness as they reached us, then the film star said, ‘Hey, Heather, Danny, great to see you.’ Huh? He knows my name? Danny stuck out his hand and they slapped their hands together in a man-shake. I thought that maybe someone would help me out a bit and refer to him by name, but it obviously wasn’t going to be Danny. Maybe my polite brother would come up with the goods. Or maybe not. Everyone turned to me and I felt the heat rise up into my face, aware that I was only wearing a bikini and everyone else was fully clothed. I opened my mouth and what I can only describe as a squeak came out. ‘Hi.’ My face was on fire. The guy was looking at me, his mouth closed, his eyes locked into mine. I saw them move off my face and they flicked downwards, just for the tiniest of moments, and the corners of his mouth moved up and I could have died; I was cringing, my whole body tensed up, all I wanted to do was bundle myself up into a ball and roll away, like a woodlouse. ‘Don’t you remember me, Heather?’ he said. His voice was low and mocking. ‘Yes. No. Um.’ I was acting like a moron. ‘I mean, it hasn’t been that long. I know I’ve changed. You have too.’ He raised his eyebrows and smiled properly at me now, with dazzling white teeth and then it hit me. ‘Matteo? Oh… oh. Yes. Sorry, I’m so. Sorry…’ ‘Matt. Just Matt now.’ Oh, thank God for that. I did a little nervous laugh and then stepped on my own foot, wincing with pain and falling backwards, stumbling to right myself. Impressive, I know. The moment broke and everyone ignored me. The boys took off their tops and jumped into the river. While they were busy splashing around and ducking each other under, I dipped my hands into the water and splashed it onto my face. I swear I could hear it sizzle as it came into contact with the burning skin. Matt looked so different. Not surprising really - the last time I’d seen him, he was a little boy. Now he was… well… a man. I guess. A very, very good-looking man. I shook my head to clear it and slipped into the river, steering clear of the others, swimming along the shady edge near the reeds. I kept dipping my face down into the water until I could be sure I’d returned to normal. OK. Good. No more squeaking. It was only Matt, after all - Ali’s best mate from primary school, the little smiley fellow we’d known for years. This was new territory for me. Most of the girls my age, at Fromedale and the town girls, had been talking for yonks about which boys were good-looking and a lot of them had kissed boys, some even more than that. I don’t know why, maybe because I had a boy as my best friend, maybe because Ali was the main object of lust in Middon and Fromedale, but it all seemed to have passed me by. Until Matt Lorenzi. I snuck a look at him, quickly turning away my head before anyone noticed. Had anyone clicked, when he nearly made me fall over? Ali might not have – I wasn’t the greatest at meeting new people, he wouldn’t read too much into my half-wittish performance. But Danny was a different matter. Danny knew every thought that passed through my stupid head, and up until now that hadn’t been a problem. I couldn’t handle Danny knowing about how Matt made me feel. It was toe-curling. It was cringeworthy. Also, it was none of his business – it was my crush, my secret. Somehow, I had to try to block Danny. I had no idea if it was possible but I knew that it should be possible. I mean, the whole telepathic thing between Danny and me was so incredible, surely making it stop should be… well, credible? Anyway, I had to try. I dried off by the side of the river, lay on my stomach in the shade, pretended to read my book and tried to clear my mind. Behind me, I heard someone climb out of the water and pad over to where I was lying. Funny, the way your heart seems to drop into your stomach, even when you know it’s not possible. ‘Hey, little sis, what’re you reading?’ Ali sat down in front of me and I held up the book for him to see - A Room With A View. ‘Like it?’ ‘Yep. S’good.’ ‘Might be even better if it wasn’t upside down.’ I made a face at him and turned it the right way up. More splashing as Danny and Matt followed Ali out of the river. Telling myself to breathe, I turned back to my book. I took my time finding a bookmark and putting it away in my rucksack, dithering about for ages until I thought everyone would be dry and dressed again. I tried to blank everything out of my mind, especially about Matt. This could be working. When I looked up, everyone was sitting on the grass and Danny rolled his eyes at me. It’s not working, Sullivan. What? What d’you mean? Pause. He’s not that great-looking. I didn’t say he was. Sometimes it was brilliant, between Danny and me, and sometimes it was dead annoying. This was new, though - he could hear my lustful thoughts about Matt and it was the first time that had ever happened. I struggled for a few seconds with my embarrassment and then decided that Danny could get lost, I didn’t care what he thought and if I wanted to look at a very fanciable guy, then I’d just go ahead and do it. Oh, great, that’s just great for me then, now I have to experience your girly panting. I’m not doing “girly panting”. He’s just… easy on the eyes. Gross. I’m going to be sick. Yuk. Get out of my head, Green. I would if I could, Sullivan. I gave him a look, hard into his eyes. There’s something about Danny’s eyes, they’re kind of mesmerising. I’ve never seen eyes that colour before or since: the brightest blue with a ring of darker blue around the edge. But they change all the time - sometimes they’re flat and like ice; sometimes they shimmer like the sun on the sea. I made a face at him, which Ali caught but ignored. He was used to us. Matt saw it too. ‘What’s the in-joke, Heather?’ He looked between Danny and me a few times, a line on his forehead, squinting at us. ‘Wait a minute. Didn’t you two… wasn’t there? Wait. You mean, you can still do that freaky thing? Use The Force?’ Danny, Ali and I froze. Matt was kneeling up now, excited, his eyes lit up. Did you tell him? No. Did you? No. Danny and I turned our heads slowly to Ali, who was cringing at our thunder-faces. ‘It was ages ago, before he left - we were best friends. Sorry. I didn’t think… I didn’t think it was a big deal. If he knew.’ I said, ‘Of course it’s a big deal. No one knows. No one’s supposed to. We told you that.’ Matt said, ‘So it is true then? You can hear each other’s thoughts? That is wicked.’ He looked at us. We were glaring at Ali and it was the first time in my life that I remember being really, truly angry with my brother. ‘Oh, come on, it’s no biggie. I almost forgot about it. Come on you two, you can trust me, I won’t tell.’ Danny growled, ‘How can we trust you? We don’t even know you.’ ‘Sure you do, man, we go way back. Lighten up.’ Now I was starting to get angry with Matt, too. Sure, it wasn’t his fault that Ali had told him, plus it was so long ago, but frankly Matt didn’t seem the type to keep his mouth shut, and Danny and I had decided right from the start that no one should know about our silent talking. Ali was the only one who knew. He’d suspected there was something strange about the way we behaved with each other, and then it had come to a head one day when we’d been playing Trivial Pursuit and I’d correctly answered an obscure question about Donald Bradman. Ali realised that there was some secret way of communication between Danny and me (I knew nothing about cricket and Ali and Danny were massive fans, walking Wisdens). We’d never told our mums or any other friends: we didn’t want to freak anyone out and it was none of their business. We thought they’d never believe it anyway. Only now we found out that Ali had told Matt. And Danny was right, we didn’t know Matt at all. We did not “go way back”. We‘d been nine years old when he’d left Middon and he’d been Ali’s friend, not ours. We couldn’t possibly trust him with this. But we had to. Bummer. Matt pulled a cigarette pack out of his shorts pockets and offered it around. No one wanted one, so he lit his own and grinned at us. ‘Think of the things you could do. Cheat in exams. Lie to your parents and get away with it. Be each other’s alibi. Awesome.’ Ali said, ‘Nice touch, Matt. Everything you’ve just suggested is either illegal or immoral.’ Matt looked at Ali to check he was joking. He wasn’t. My brother, sixteen going on thirty-six. ‘Don’t make me more sorry I told you, OK? Danny and Heather have managed to keep this a secret for fourteen years, only you and I know, so you need to make sure you keep it that way. All right?’ ‘All right, man. Chill out. Like I said, you can trust me.’ He took a drag on his cigarette. ‘Tell me how it works though.’ We just stared back at him. Ali had never straight asked about it. We reckoned he only half-believed it was real; he was far too logical to ever believe something so inexplicable. We’d never talked about it ourselves, because it had always been there and we didn’t know why and we didn’t question it or need to understand it. Most of the time, we had no idea if we were speaking out loud or in our heads. ‘Tell me. How does it work? What’s it like?’ Ali sat up, interested too. Danny looked at me and I shrugged. Matt said, ‘Right, so what did you say to each other then?’ ‘Well, Heather said to me, “Is Matt the biggest tosser you’ve ever met?” and I replied, “Without a doubt.”’ ‘Oh ha ha.’ Matt looked away from us, put his fag in the corner of his mouth and lay on his back, his hands behind his head. He squinted up at the sun. I swooned, just a little bit. ‘You may as well tell me. It’s basically the most interesting thing there is going on in this town.’ He turned on his side towards us and propped his head on his elbow, waiting. I said, ‘It’s not that interesting. It’s difficult to explain. Umm. It just sort of happens. Like you’re having a conversation in your head with yourself, you know? Except there’s my voice and there’s Danny’s voice.’ ‘When did it start?’ ‘Dunno. I don’t remember it starting. Maybe when we moved to Middon; I was one year old, right, Ali?’ He nodded. ‘So maybe it was then - we moved next door to Danny and we used to play together. I think it was always there.’ Matt frowned. ‘So all the time before, when I was in Middon, when we were at school together… you two were just having your own conversations?’ Danny and I nodded. Ali asked, ‘Do you have to be near each other? In the same room? Touching?’ ‘Yeah. Sort of like - the closer we are, the clearer the signal.’ Matt said, ‘Is that why you’re holding hands?’ We both looked down at our hands. I hand’t noticed we were doing it. I blushed. Danny edged his hand away from mine. ‘Are you two… you know? Together?’ Danny’s face was like a tomato, the spots and the blush merging. ‘No. It’s not like that.’ I said, ‘We‘re just friends.’ ‘Yeah, right. Never thought about it? That would be creepy, right, if one of you was thinking about the other one, naked, and then…’ ‘OK OK, that… no. Stop. Stop, OK? That would never… it’s not like that.’ ‘Then why have you both gone red? That is so cute. You two should definitely get together.’ ‘Shut up, Matt,’ Danny and I both yelled at him. His words were churning and twisting, blaring inside our heads. My face was flaming again. Danny was fuming. Even Ali looked like he was about to blow a fit. But Matt blithely ignored us. ‘So… you’re telling me that you’ve been able to see into each other’s heads for your whole lives and you’ve never thought about doing it with each other?’ That was when it happened. It was like a rock falling from the sky, slamming into my brain, blocking out the light and the sound and afterwards, there was a silence I’d never known. A blank space, a cool emptiness that felt soothing and scary at the same time. I don’t know how and I don’t know why, but for the first time in my life I couldn’t hear Danny. * If you'd like to read on, please download the ebook by signing up for my mailing list. I've had the first chapter of 'No Number Nine' translated into German by Nicole König at Ecoquent and was very excited to show it to publishers and agents at the Leipzig Book Fair. Now that event has been cancelled and I'm gutted. If there are any German agents or publishers looking for a new book, please get in touch and I'll send you an English book, the German chapter and my Expose.

It's coming up to a year since I published No Number Nine, so to celebrate, here's the first chapter of the book for you to read, as a taster:

Warning! Content suitable for over 18s only. No Number Nine by F. J. Campbell This book is set mostly in Munich, with a mix of characters from Germany and all over the world. Most of them speak, to some degree or other, German and English. For the purposes of not annoying the crap out of the reader, it’s assumed that, unless otherwise indicated, everyone involved in every conversation understands the language being spoken, whether that’s German or English. CHAPTER ONE Munich, September 1999 Philippa Mitchell was eighteen years old when she left England. She left behind her bedroom, that cocoon of misery in which she’d imprisoned herself; her parents, with their forced, hollow cheerfulness; and the pieces of her heart, smashed to smithereens two years ago with a phone call that came in the middle of the night. Without a backwards glance, Pip was gone. She’d spent most of the last two years in her bedroom, venturing out only to go to school. Now she was escaping from her bedroom, her house, her town, her country. As she sat in the train speeding south from Munich airport towards the suburbs, she reread her instructions from Mr von Feldstein. She’d spoken to him on the phone and he’d written this letter, detailing her childcare duties and apologising for not being able to collect her from the airport. The letter was polite and businesslike. In it he’d written, Mrs von Feldstein is currently living elsewhere. In other words, she’d left him. There might be a million fascinating reasons why Mrs von Feldstein was Elsewhere, but Pip didn’t much care about any of them. What she cared about was this job, which she needed, and which she would lose if Mrs von Feldstein took it upon herself to return from Elsewhere. At Solln station, Pip stepped off the train, slinging her rucksack onto her shoulders. It wasn’t heavy – she didn’t own many clothes and she’d ditched everything else. Letters, books, photos, CDs. Too many reminders. She walked along the quiet, tree-lined road away from the station, and within a few minutes found Number Three, Emil-von-Feldstein-Weg. It hadn’t clicked before, but it now it did: the family she’d come to work for was ever-so-slightly loaded. Number Three wasn’t a house, it was a mansion. And the street was named after someone in their family. Who has a whole street named after them? She stood opposite the house, gawping at it. It was set back off the road, with high hedges surrounding it. Through the gates she saw a gravel driveway which swept around to stone steps leading up to an arched front doorway. She craned her head around the bars of the gate, up past two storeys to the roof, which was covered with four dormer windows of different shapes and sizes. The garden went on for miles. And was that a swimming pool? Bloody hell. ‘Hello, are you Philippa?’ A voice behind her made her jump. She turned to see a middle-aged lady with grey-streaked hair smiling at her. Pip gulped. Surely this couldn’t be…? She stammered, ‘I prefer Pip. Are you… Mrs von Feldstein?’ The woman nodded and held out her hand. Pip shook it despondently. So she’s come back, has she? Oh, great. Pip would have to go home again. ‘I wasn’t expecting… I thought you…’ Mrs von Feldstein waited, not understanding. Pip searched for the phrase from the letter. ‘I thought you were… currently living elsewhere.’ ‘Me? No. Oh… I’m not that Mrs von Feldstein. I’m Rosa. I’m the sister.’ She peered in a kind way at Pip, who hadn’t quite caught up yet. ‘You’re thinking of Dominic’s wife, Elisabeth. I live—’ ‘Next door. Of course, yes, Mr von Feldstein mentioned you in his letter.’ My wife’s sister Rosa lives next door with her family.She thought, Thank Christ for that, and said, ‘Sorry.’ ‘Nothing to be sorry about.’ Rosa pushed open the gate. ‘Come on in. So you know about the family situation, from Dominic’s letter? He told you about everyone? The boys, too?’ Pip nodded as they crunched along the drive. The boys. We have two sons at home, Maximilian (10) and Ferdinand (8). They go to the International School, a fifteen-minute walk away, where you’ll take them and pick them up every day except Friday – on Fridays I like to do it myself.‘I know all about them.’ Rosa said over her shoulder, ‘You won’t know what’s hit you. Come next door to my house if you ever need a break from the testosterone.’ She pointed to a wooden gate tucked into the hedge. ‘We have two girls, Isabella and Anna. You’re always welcome. I hope you know what you’re letting yourself in for.’ Pip reckoned she could handle two little boys, whatever Rosa might think. ‘So, Dominic will be back tomorrow evening with Max and Ferdi. They’re away at the lake house tonight. Until then you can settle yourself in.’ She unlocked the front door and they stepped into a large hallway. Pip took it all in: a grand staircase of dark, highly polished wood ahead of them, and doors leading off the hallway to the left, right and either side of the stairs. Rosa opened them in turn and motioned for Pip to follow. ‘Living room, dining room, kitchen on this floor. That door,’ she pointed to the left of the staircase, ‘goes down into the cellar, where your room is. Leave your bag there – good gracious, is that all you have? I’ll show you upstairs first.’ At the top of the stairs, Rosa pushed open the two doors to the left, which were covered with stickers and postcards. ‘Max here, Ferdi there, or maybe the other way round, I can never remember. You’ll need to get these boys in hand – I’ve never seen such chaos.’ It was true – in both boys’ rooms, it was impossible to see the colour of the carpets. There were Lego models and train tracks, comics and bean bags, clothes, towels and shoes strewn over every surface. Pip liked the chaos; it made her smile to think that these two small worlds of disorder had been created. She thought – she hoped – that Max and Ferdi were going to be fun to look after. Rosa sighed and closed the doors again, as if by doing so it would make the mess go away all by itself. ‘Bathroom’s there.’ She pointed to the doors on the other side. ‘You don’t need to worry about those two.’ And then she did the strangest thing. She winked at Pip. Wrong-footed, Pip guessed the doors must lead to Mr and Mrs von Feldstein’s room and maybe a guest room. Rosa was looking at her like she expected a reply, so she tried to smile. ‘They’re not fans of Lego?’ It seemed like she’d said the right thing – Rosa chuckled and turned to go downstairs. Pip, remembering the dormer windows, pointed to another door they hadn’t been through. ‘Where does that go? To the attic?’ ‘Yes, that’s Dom and… well, Dom’s room. Also his bathroom and office. You won’t ever need to go up there; he likes to have his own private space. I can show you, if you like?’ ‘No, not if it’s private.’ Pip followed Rosa downstairs, where Rosa scooped up her rucksack and opened the door to the cellar. ‘Essentially, this is all yours. Although as you’ll see, there are other storage and laundry rooms down here. Martina – that’s the cleaner – comes twice a week. She cleans the house and does the laundry. Your bathroom is here.’ Rosa moved along the dark corridor, flicking on light switches. ‘Door to the garden.’ She ran her hand along a row of four closed cupboards. ‘In here are winter clothes, spare bedding et cetera. The boys store their spare sports stuff here sometimes. It gets a bit smelly, as you can imagine.’ Pip couldn’t imagine. What stuff? How smelly could two small boys be? Rosa continued, ‘Of course, they have lockers at the club, but they have so much kit, some of it inevitably ends up here.’ Kit? Club? What was Rosa going on about?Pip couldn’t remember reading about clubs in the letter. Must be tennis or golf, something posh. She pictured a country club with gym-toned socialites wafting around in pristine tennis whites and jewellery, drinking G&Ts. Elisabeth would no doubt be captain of the ladies’ tennis team, highly competitive on the court and prone to cheat on line calls if she ever found herself at thirty-forty down.Pip, not wanting Rosa to think she was obtuse or inattentive, didn’t ask – she wanted to read the letter again, make sure she hadn’t missed something obvious. Her German was good, or so she’d thought, but there was obviously something she hadn’t understood properly. Rosa pushed open a door at the end of the corridor and switched on the light. ‘This is you.’ The room was large, with a double bed low to the floor, a squishy-looking sofa covered in bright cushions, a widescreen TV, a DVD player, a desk with a laptop on it, and a huge wooden wardrobe. She stood rooted to the spot in shock. This house, this room – it was insane. She thought of the tiny house she lived in with her parents. You could fit the whole of the ground floor into this one room. ‘This is all for me?’ ‘You like it? I can’t tell.’ ‘I love it,’ breathed Pip. ‘Wonderful. For a moment it looked like you couldn’t quite believe what sort of a place you’d landed in.’ She gave Pip two keys. ‘One for the front door, one for the back – that’s your own private entrance, should you need it.’ She looked at her watch. ‘Oh hell, I said I’d be back at the shop at two. Can I leave you? Take a look around, settle in, unpack… enjoy the peace and quiet before the multitudes descend tomorrow.’ She hurried to the door. ‘Wait! All this is mine? The TV, the laptop? Or is someone coming to pick it up?’ Rosa waved her hand around the room dismissively. ‘All yours to use while you’re here.’ Pip blinked and started to say thank you, but Rosa had already disappeared. The sound of her footsteps faded up the stairs and across the hallway, the door slammed, and Pip was alone in the silent house. * She roamed around the house, exploring each room again. Everywhere except for the attic, Mr von Feldstein’s private domain – she didn’t dare. The two mystery rooms on the first floor were definitely guest rooms. On the wall of each hung one painting, different perspectives of the same castle; the beds were neatly made with crisp white linen; and the wardrobes were bare except for a pair of spare pyjamas and a couple of shirts, probably Mr von Feldstein’s. In the boys’ rooms, she hung up damp towels and folded crumpled clothes. She took some cups and bowls downstairs and stacked them in the dishwasher. May as well make a good first impression. The kitchen was – apart from her own – her favourite room. Like something out of a magazine. It had an island unit in the middle, and along one wall there stood an enormous wooden table with six seats on one side and a bench on the other. Above that, the wall was a blackboard covered with chalked messages. She’d come back to those later. French windows, through which streamed late-afternoon sunshine, led out to a patio. Beyond the patio was indeed a swimming pool, a long, thin one for doing lengths in. Shame she didn’t own a swimming costume. She’d grown out of her old one and never replaced it. The house was light and modern inside, all floor-to-ceiling windows and stripped wooden floorboards. Everything looked understated but expensive. In the living room, there were shelves and shelves full of books and DVDs, which she felt like hugging, so she did. The walls were white and bare except for one single painting of the same castle as upstairs, with a lake in the foreground and a field of lavender in the background. Pip caught a faint whiff of fresh paint – maybe they’d redecorated recently. There was something missing. What was it? She couldn’t decide, and it bothered her. Outside, she’d expected the lawn to be pristine, but it was dotted with patches of bare, scuffed earth, reminding her of the makeshift football goals in the park near her parents’ house. She found the back door, her own private entrance into the cellar, next to it an old stone bench covered in moss. In her cellar corridor, where Rosa had said the spare ‘kit’ was, she opened a cupboard door to find winter coats and trousers, ski boots, skis and poles in different sizes. In the second cupboard, there were tennis racquets, golf clubs – aha – Frisbees, footballs and some oars. There was a bit of a sweaty odour to it, but nothing she couldn’t handle. When she opened the third cupboard, though, it nearly knocked her out – there were about twenty pairs of trainers and Rosa hadn’t been kidding about the pong. It was like something had died in there. It was sour and rancid, like decaying vegetables and rotten eggs. Pip recoiled, slammed the door and didn’t dare look in the fourth cupboard. In the kitchen, joy of joys, there was a fancy-pants coffee machine. It looked like something you’d see in an Italian café – stainless steel, nozzles, buttons with pictures on, the works. Pip loved coffee. Was there anything better in the world than the smell of coffee? She peered at it, trying to locate the On button. Terrified of breaking the machine, her fingers hovered over a few buttons but her nerve failed her and she gave up. The blackboard was a mess of scribbles and smudges. There were messages written by the children: Dun my homworkand Wear are my lukky sox. There were dates and places: Konstanz, Padua, Berlin, Amstelveen. 15 September – 1October, circled many times over. Why did those dates mean something to Pip? A section of the board was covered with random names: Pim, Shiver, JJ, Henry, Obermann, Rollo– some crossed out, others underlined. And there, in the corner, was her name. Someone had drawn a smiley face next to it. One of the boys, maybe, looking forward to her arrival? It startled her to see her name amongst these cryptic messages from strangers’ lives. * That night, Pip lay exhausted in bed, her senses bombarded by the newness of her life. The expectation of tomorrow hung over her like a thrilling promise. She fell asleep around eleven. Next thing she knew, a banging sound woke her. Shit. What was that? The front door? Pip checked her watch – 2am. Who was coming into the house at this time? Rosa had said the family was arriving tomorrow evening. Were they back early? Pip didn’t know what to do. Should she go up and say hello, or pretend to sleep? What would a normal person do?The door had slammed pretty loudly, so they must have known it would wake her. She dragged herself up out of bed and found a baggy old sweatshirt to pull over her pyjamas. Halfway up the cellar stairs, she heard another sound. A giggle. Murmuring and another giggle, louder this time. She frowned. Was that the kids? It didn’t sound like children. It sounded like a woman. She paused. Better go back to bed. It couldn’t be burglars, could it? Not laughing like that? She waited, listening to feet moving upstairs. Oh crap, if it was burglars, what was she supposed to do? Had her parents ever told her what to do in a situation like this? If they had, she hadn’t been listening properly. She crept back to the second cupboard and opened it quietly. By feel only, she found a golf club and eased it out without dislodging anything else. Those giggling burglars were going to get it, if they tried any funny business with her. Slowly, slowly, Pip pushed open the door to the hallway. It was dark and empty and absolutely silent; the kind of silence where no one is there. She heard noises from upstairs, a thump and a laugh, a man’s this time. She waited at the foot of the stairs, gripping the golf club, listening. Before she knew what was happening she was at the top of the stairs, her heart thudding in her chest, edging swiftly and quietly towards the room. A strip of light under and around the slightly-opened door. One foot in front of the other, closer and closer towards the room. Rustlings, a whisper and then nothing. With the tip of her finger, Pip nudged the door open, minuscule prods, just enough to see into the room. And when she saw it, she felt a great crashing in her ears, blood racing to her head as she gripped the door frame to stop herself from keeling over. Lying naked on the bed, long blonde hair streaming over the pillow, was an unbelievably beautiful girl. Her eyes were closed, her hands pushed against the wall above her head, her hips slightly raised. Between her legs, a man’s head with short muddy-blond hair; clasping her breast, one of his hands. From the girl’s mouth issued a series of low moans, becoming ever louder, as she began to buck her hips and slam her head on the pillow. Pip’s eyes burnt as she reversed on iron-heavy legs out of the room. They hadn’t seen her. They couldn’t have. Please please please let them not have seen her. All she had to do was make it downstairs without them hearing her. She tiptoed down each step in time with the moans, to cover any creaking noises she made. At the bottom of the stairs, she heard a sound that she’d never heard before. It was like the girl was dying. A long, coarse shriek that made Pip think of endless pain. Was he killing her? Was that what sex sounded like? It wasn’t supposed to hurt, was it? She slipped through the cellar door, raced back along the underground corridor and dropped into her still-warm bed. Oh God. What had she done? Who was that girl? Who was the man between her legs? She couldn’t expel the image of them together. The girl’s skin, her hair, her doll-like perfection, her eyes scrunched shut in absolute ecstasy. Was she real? Had Pip really seen it? It was outrageous, she felt sick, but why couldn’t she stop thinking about it? The sound of it more than anything – that girl had howled like an animal. Jesus. And who the hell was the man? Surely it couldn’t be Mr von Feldstein? For obvious reasons, she hadn’t managed to see his face. But surely… what was he doing? That girl was Pip’s age – no way was she the missing Mrs von Feldstein. He had a lover! Or was she a prostitute? Christ almighty, what kind of a place had she landed in here? For hours, Pip lay trembling in bed, trying to calm down, forget about it and go to sleep. But racing through her head were the questions, the pictures, the utter mortification and panic if they’d seen her. She was dreading tomorrow – how could she meet Mr von Feldstein, how could she look him in the eye and take care of his children after what she’d seen? * When she woke up in the morning, her first thought was of the couple. What to do? Not hide in her room all day, that’s for sure. She’d promised herself that part of her life was over; she had to get up and face… whatever it was she had to face. She showered and dressed, took some deep breaths and walked upstairs. There was no one in the hallway. She looked in the kitchen. Empty. The house was quiet. Outside she heard the faint whoosh of a car passing by on the road and some birds tweeting. ‘Hello?’ she tried. ‘Hello? Anyone there?’ Her German sounded like a made-up language – gobbledygook that a child might speak. It left her mouth and dissipated into the corners of the hallway. No one answered. She looked out of the front door – no car in the driveway. ‘Hello?’ she said again, this time louder. There was no reply from upstairs. No voices or strange, ethereal sex sounds. Nothing. Right, thought Pip, that’s it. I have to go and look. She stomped up the stairs, loudly and slowly, to give them time to get dressed or whatever. ‘It’s me, Pip. The new au pair. Is anyone there?’ Her heart was thumping as loudly as it had last night, but this morning she felt, more than anything else, angry that she had to act like this. Bloody sexers. Couldn’t a person come to a new job without having to see a live sex show within hours of arriving? What was the world coming to? The spare-room door was wide open and when she looked in, there was no one. Last night – had she imagined it? Was it one of those dreams? A wet dream? But didn’t only boys have them? Wait – she hadn’t left the door open yesterday afternoon, when she’d been exploring. Or had she? OK. Maybe she hadimagined it. Weird. She’d never had a dream like that before. Hang on. No – the room didn’t look the same. She walked in and examined the bed: it was made, but not expertly. Yesterday, the white covers had been stretched over it and tucked in neatly. Today they were pulled in a more haphazard way over the bed. And there – aha! A blonde hair on the pillow. Bright, shiny, long – definitely the girl’s. Pip’s mind was racing. Two people had been here, in Mr von Feldstein’s house, having noisy sex. They’d entered and exited secretly, thinking no one had noticed. It couldn’t have been Mr von Feldstein – why would he bring a girl back here and not use his extremely private bedroom in the attic? It must have been burglars. Sex burglars. Was that a thing? It was now. Pip searched the house, examining every window catch, checking every lock. Outside, there were no ladders or footprints in the flower beds. She couldn’t wrap her head around it, so she had some breakfast. Making no more headway with the coffee machine than yesterday, she had to be satisfied with a couple of deep sniffs. Then she decided a walk might be just the thing. The sun was out, bathing everything in a mellow glow. Emil-von-Feldstein-Weg was a street of large houses, Rosa’s next door a match with Number Three, minus the attic windows. Pip wandered past the station, a bookshop, a bakery and – wonder of wonders – a small cinema. She peered in the window. It was one of those cool art house cinemas that showed interesting foreign films. There were posters in the window for films called Lola Renntand Todo Sobre Mi Madre, which was being shown with German subtitles. After half an hour, she found the river. Sitting on a bench, she watched the water rush by. Despite the sunny day and the pretty view of the tree-lined River Isar, the contented dog-walkers and the chattering families cycling by, she couldn’t shift the feeling that this whole au pair idea was a colossal mistake. What was she doing here? This family, this house – even without what’d happened last night, she didn’t belong with them. But where did she belong? Would she ever be happy again? She’d forgotten what it felt like to be happy. FADE IN EXT. A BENCH, BY A RIVER – DAY PIP MITCHELL, medium height, plain face, straight up-and-down body, mousy-brown hair – sits watching the river, fat tears rolling down her face. PIP (mumbling) I wish you were still here, Holly. I miss talking to you. I don’t have anyone to talk to. HOLLY MITCHELL, 25 years old, beautiful, short dark hair, fit and tanned – sits next to her and puts her arm around her. HOLLY I’m here, kiddo. What d’you want to talk about? PIP I don’t know what I’m doing here. I’m lonely. I’m sad. I’m a pathetic loser. And I don’t know what those people were doing last night. HOLLY (laughing) He was going down on her, kiddo. You should try it sometime. It’ll make your brain explode. But seriously, don’t give up on Munich yet. This is a good place to be. You’re not pathetic – you’re brave. PIP I can’t do this without you. It’s too hard. I want to see you again. HOLLY Not going to happen, sis. Even I can’t manage to come back from the dead. PIP You can. You have to. You’re my hero. You’re my big sister. I need you. Pip sniffs and wipes the back of her hand under her nose. Holly hands her a tissue. She blows noisily into it. PIP Thanks. HOLLY Whatever you need me for, I’ll be here. Tissues, careers advice, Sex Ed, anything. Stick at this job, you’ll see, it’s going to be just what you need. No more moping about me, OK? Promise me? PIP ’K. Promise. HOLLY And remember what I always say: if it doesn’t scare you shitless-- PIP It’s probably not worth doing. Yeah. Thanks. HOLLY That’s what big sisters are for, kiddo. That and buying you booze when you’re underage. Holly stands and walks towards the river, turns and waves at Pip. She walks into the water until it reaches the top of her head. She disappears. Pip sat a while longer, hating the scooped-out feeling she always had after she’d been crying. Then her stomach rumbled. She walked away from the river, following the path back up towards the house. Along the way she passed a beer garden, full of people eating at wooden tables in the sunshine. Her mouth watered. She wished she had enough money to eat there, but she had to save every last penny this year. Every last Pfennig. There was bread and cheese at the house and that would have to do. She wasn’t allowed to eat out; she had to be careful or she’d never afford the flights to Australia for next year. * All afternoon, Pip jumped at the sound of cars on the road, scampering to the front door to check if it was the family arriving. She steeled herself to meet Mr von Feldstein. If he had the same hair as the man in the bed last night, she would have to put a brave face on. She couldn’t go back to England. She’d never find a job as well paid as this one, with free accommodation and food, so however strange the family was, she had to stick it out. Plus, she’d promised the fabricated ghost of her dead sister that she’d make a go of it. At five o’clock, she was lying on the sofa with a book when she heard a car on the driveway, doors slamming and children’s voices. Brace yourself, Pip. Smile. Think of the money. She was in the hallway when the front door burst open, two boys careering into the house, shouting and jostling each other. They were alike, with dark curly hair and brown eyes. ‘Dad! She’s here! Hello. Dad! Are you Pip? Why are you called that? How tall are you? Do you know Harry Potter? Why are you a girl? Where are you most ticklish?’ ‘Umm. Yes. I don’t know. About five foot seven. Who’s Harry Potter? Because I am. None of your beeswax.’ ‘Dad, she doesn’t know Harry Potter. Da-ad. Can we send her back?’ Pip heard footsteps clomping up the stairs outside the front door and held her breath. Here we go. Mr von Feldstein’s hair was curly, dark and greying. Definitely not him.Thank Christ for that. He put down the suitcases and held out his hand to Pip. ‘Welcome and sorry about these two monsters. (No, we can’t send her back.) How was your journey? (Take your stuff upstairs and stop badgering her.) Did Rosa show you your room? (I don’t know whether she likes Star Wars.)’ He smiled wearily as the boys trooped upstairs. ‘I’m dying for a coffee. Would you like one?’ *** Hope you enjoyed that - comments below, please! If you liked it, I can post a second chapter, but after that if you want more, you'll have to buy a copy. xx FJ Hello - The Islanders is my new novel, and here's a snippet from the beginning of the book, so you can read it and see if it's for you.